On October 5, 2017, EUObserver reported that the European Union was seeking a dialogue with INTERPOL to find a way to stop the abuse of its resources by countries that use INTERPOL to persecute political opponents and other victims of unlawful criminal prosecutions. The call for negotiations followed the recent detention of Dogan Akhanli, a German-Turkish writer, and Hamza Yalcin, a Swedish-Turkish journalist. Spanish authorities detained them at Turkey’s request disseminated via INTERPOL’s channels. Akhanli and Yalcin fled Turkey many years ago and were granted refugee status in Europe.

On October 5, 2017, EUObserver reported that the European Union was seeking a dialogue with INTERPOL to find a way to stop the abuse of its resources by countries that use INTERPOL to persecute political opponents and other victims of unlawful criminal prosecutions. The call for negotiations followed the recent detention of Dogan Akhanli, a German-Turkish writer, and Hamza Yalcin, a Swedish-Turkish journalist. Spanish authorities detained them at Turkey’s request disseminated via INTERPOL’s channels. Akhanli and Yalcin fled Turkey many years ago and were granted refugee status in Europe.

In seeking the dialogue, the European Union leaders expressed their desire for a proper review of INTERPOL red notices. They have also indicated that the need exists for an effective redress mechanism for the victims of INTERPOL abuse.

On October 16, 2017, EUObserver published an op-ed titled ‘INTERPOL and the EU: don’t play politics.’ Its authors, Rutsel Sylvestre J. Martha, an INTERPOL’s former General Counsel, and Stephen Bailey, argue that the INTERPOL General Secretariat already conducts a proper review of red notices before their publication and an effective redress mechanism is already in place.

Indeed, INTERPOL must ensure that red notices comply with its rules. Every year INTERPOL processes numerous requests to locate and detain individuals. It would seem possible for the organization to review every red notice for its compliance with such minimum requirements as the nature of the charge behind the notice and make sure the identity particulars, the description of the facts of the case, and a reference to the country’s criminal statute and a valid arrest warrant accompany the red notice. However, taking into consideration the high volume of information INTERPOL processes on a regular basis, it cannot possibly look into all the circumstances behind each and every red notice to make sure none is politically motivated or doesn’t otherwise violate the organization’s rules prior to its publication. This is also true with regard to the compliance review of randomly selected already published red notices. In addition, the authors of the op-ed don’t mention the so-called “diffusions,” which, like red notices, may be used as requests to locate and detain individuals for the purpose of their extradition and may be disseminated among a large number of INTERPOL member countries. However, unlike red notices, governments can send diffusions via INTERPOL’s channels without any prior review by the General Secretariat. Because of the lack of oversight prior to their publication, diffusions represent a more attractive means for governments that abuse INTERPOL’s resources, and as such, they pose an even higher risk than red notices.

In claiming there is an effective redress mechanism for the victims of INTERPOL abuse, the authors of the op-ed mention the right of an individual to access, correct, and/or delete information in INTERPOL’s files. It is important to remember that the right to access the information in the organization’s databases is subject to the government’s consent to disclose such information to the individual. This is also the case with any evidence and other information the government submits to the Commission for the Control of INTERPOL’s Files, an independent body with the exclusive power to adjudicate requests from individuals seeking access to, correction, and/or deletion of information in INTERPOL’s databases. The Commission discloses the evidence or other information the government submits in response to the individual’s request if the government agrees to such disclosure.

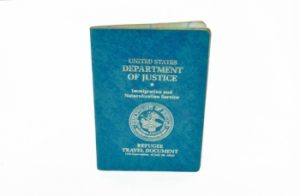

The authors of the op-ed rightfully point to the reforms INTERPOL has recently carried out to expand the rights of individuals. However, despite the reforms, the existing redress mechanism still lacks some crucial safeguards inherent to the modern democratic due process, such as the right to a hearing and the right to appeal. In June 2014, the INTERPOL Executive Committee endorsed a new policy on refugees. According to the policy, “in general, the processing of red notices and diffusions against refugees will not be allowed if the following conditions are met: the status of refugee or asylum-seeker has been confirmed, the notice/diffusion has been requested by the country where the individual fears persecution, the granting of refugee status is not based on political grounds vis-a-vis the requesting country.” Although the policy is a significant step towards protection of refugees from INTERPOL abuse, it needs improvements. For example, the policy doesn’t grant refugees an exception to the rule that INTERPOL doesn’t disclose whether there is information about the individual in its databases without the government’s consent. As a result, refugees, like other individuals, often learn about a red notice or diffusion against them after they are detained due to the INTERPOL alert. In such cases, the rights provided in the policy come too late. This is one of the reasons why the detention of refugees like Dogan Akhanli and Hamza Yalcin continues despite the fact that the policy has been in place for several years.

It has been reported that INTERPOL has refused to cooperate with Russia in the case of Grigory Rodchenkov, the former head of Russia’s anti-doping laboratory-turned-whistleblower. Mr. Rochenkov has publicly accused the Russian government of running a doping scheme during the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. Mr. Rodchenkov’s case may look like just another government trying to abuse INTERPOL’s resources to persecute a political opponent. However, it stands out because the target of the red notice is a whistleblower wanted not because of his political beliefs but because as a previous insider, he witnessed and exposed the government’s misconduct.

It has been reported that INTERPOL has refused to cooperate with Russia in the case of Grigory Rodchenkov, the former head of Russia’s anti-doping laboratory-turned-whistleblower. Mr. Rochenkov has publicly accused the Russian government of running a doping scheme during the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. Mr. Rodchenkov’s case may look like just another government trying to abuse INTERPOL’s resources to persecute a political opponent. However, it stands out because the target of the red notice is a whistleblower wanted not because of his political beliefs but because as a previous insider, he witnessed and exposed the government’s misconduct.